May 15, 2019

Preventing Farmer Suicides through Helplines and Farm Visits

by Allee Mead

In 2016, dairy farmers Meg Moynihan and her husband lost the buyer for their organic milk. Because she was working for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture (MDA) Organic Program at the time, Moynihan thought it'd be easy to find a new buyer, but “all doors were closed,” she said. “It was the beginning of the milk glut.”

Moynihan and her husband actually had to dump their milk while they explored other options: Were there other companies or co-ops they could work with? Could they buy a truck and sell the milk themselves? Should they turn their milk into cheese? After nearly two months, her husband decided to take a job as an over-the-road truck driver and told Moynihan she could sell the cows. “He said, 'I have done everything I can think of, and it pretty much feels like I have failed,'” said Moynihan. “And those were extremely scary words to hear from your spouse and from any farmer.”

At that point, Moynihan decided to take a leave of absence from the MDA and run the farm herself. It was stressful: she could feel her health getting worse, as she barely had enough time to buy groceries, much less eat healthy. In addition, she said she'd cry and slam doors at least twice a day. She sent an email to her doctor, who then helped her address her symptoms. Finally – nine months after losing their buyer – the couple found another organic milk buyer.

He said, 'I have done everything I can think of, and it pretty much feels like I have failed.' And those were extremely scary words to hear from your spouse and from any farmer.

While Moynihan's story has a happy ending, not all farm families have been so lucky. Farmers are facing an economic crisis of low market prices as well as natural disasters like flooding, droughts, blizzards, and wildfires. Feeling overwhelmed by this difficult situation, some farmers have taken their own lives.

Interventions for Farmers

After Moynihan returned to work at the MDA, she told the department, “I don't want to be the organic lady anymore. I've just been struggling to be a different kind of organic lady. I don't want to do this in my other life.” The department agreed and asked her to help develop support programs for farmers experiencing difficult times.

One of the first actions the MDA took was changing the name of its Crisis Connection helpline. Moynihan explained that the Upper Midwest culture might prevent farmers from calling a helpline with that name: “Oh, yeah, this is a crisis line, you know, and I'm just feeling challenged. I guess I'm not really in a crisis. Maybe I shouldn't call this line because somebody else in crisis needs it.”

The new name, the Minnesota Farm & Rural Helpline, reminds farmers, farm families, and community partners that they can call with any kind of question, not just “crisis” questions. The helpline and website have three options: one that connects callers to counselors, one that connects callers to their local United Way for help with daily living, and one that connects callers with financial and business assistance. From July 2018 to February 2019 alone, the helpline received 57 calls, and the website had more than 1,300 unique visitors.

The services of psychologist Ted Matthews are another important resource offered by the state of Minnesota. When he talks with farmers, he helps them identify practical changes they can make to ease their stress. This strategy gets farmers to stop thinking about what they wish was happening and remember what factors of farming are in their control. In addition, he asks them to focus on the good things in their lives, like their families. “If you're focused on the positive things,” he says, “what you're doing is you're saying, 'I can make my day a little bit better than if I don't.' And 'a little bit better' beats the heck out of 'not a little bit better.'”

Matthews lists his cell phone number (320.266.2390) online and talks with farmers and agribusiness partners for as long as they need to talk. Sometimes his clients are dealing with suicidal thoughts, and other times they just need to vent. “People never waste my time,” he said. Unlike a traditional behavioral health model, there's no billing, no copay, no paperwork, and no scheduling appointments with Matthews.

Matthews also relies on word of mouth to promote his services. If farmers trust their banker or farm business management instructor, they might act on a recommendation to call Matthews. After farmers talk to Matthews, they're more likely to share his phone number with other farmers.

One time, he received a call from a woman who said her father was feeling suicidal. Matthews told her, “Tell him that you want him to call for your sake, that you're so concerned about him that it is really hurting you and it's really bothering you…and if he would call me, then you'd feel a lot better. And then let me take care of it from there.”

Matthews talked with this farmer for a couple hours and gave him information he could share with his daughter. “Now, would he have committed suicide? Who knows. The only thing I know is that he didn't,” he said.

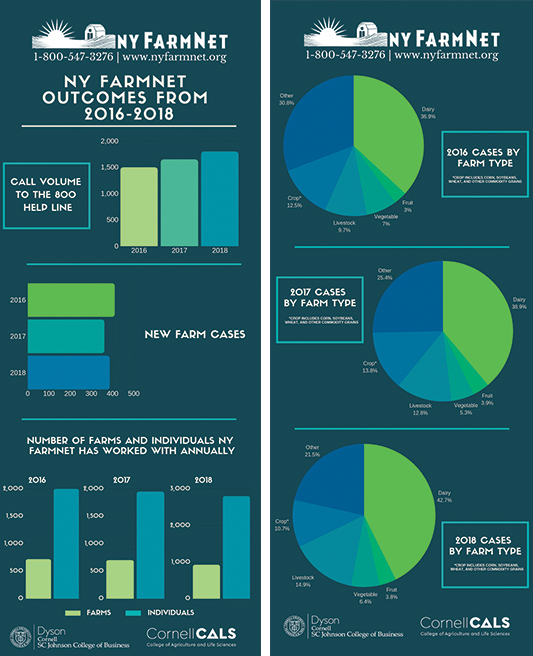

In New York state, NY FarmNet provides a helpline as well as free, confidential, on-the-farm consultations. “We go to the farmer directly instead of just asking them to take a day off to leave the farm, which they might not be able to do because they might be a one-man/one-woman show,” said Kate Downes, Outreach Director of NY FarmNet at Cornell University.

Each visit involves two professionals: a financial consultant, who can help with everything from making a budget to estate planning, and a personal consultant, who's trained in social work or clinical counseling and can help families with stress management and communication. Many of NY FarmNet's 41 consultants also have a background in agriculture, which allows for cultural familiarity.

Downes said, “There's so much that goes on with farming, and most farmers are the boss and the mechanic and the milker. They have to clean the barn, they have to keep the books, all these things. There's so much for them to think about that it's a relief when they don't have to explain themselves, really, to anyone.”

In 2018 alone, NY FarmNet responded to 1,800 requests from farmers, completed on-farm visits with over 925 farms and over 2,800 individuals, helped 64 farm families transfer their business, and helped complete 112 business plans.

We work with farmers to help them work through that loss and grief of not just losing the farm, but their identity, their heritage as a farmer.

Downes remembered one farmer who called, feeling suicidal. The financial and personal consultants visited and helped him look through his finances. They discovered that he had about $20,000 in debt – a relatively small amount compared to the debt of other farmers they had worked with. The consultants talked him through simple adjustments he could make to reduce his debt. Downes said, “Essentially, we saved his life and his farm just by helping him sift through all those things.”

NY FarmNet also helps farmers look at their operation's future profitability. If farmers decide to sell the farm, Downes said, “We work with farmers to help them work through that loss and grief of not just losing the farm, but their identity, their heritage as a farmer. We help them plan the farm sale, build a resume to find an off-farm job, help them see that there is a life after farming.”

Building Community Support for Farmers

In addition to working with farm families, NY FarmNet receives calls and emails from those who work with farmers. For example, Cooperative Extension agents have told Downes that they have received calls from farmers in crisis and didn't know how to help. A farm supplies sales manager told Downes, “I deal with farmers all the time. I should know what to do.”

Downes suggested providing Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) trainings across the state so these groups know what to do when someone is struggling. The MHFA trainings have had about 50 attendees so far, including from Extension offices, farm supply companies, health service agencies, and veterinarian offices.

This winter, Downes and the NY FarmNet assistant director traveled to Michigan for the Farm Stress Management Summit. They attended the “Communicating with Farmers Under Stress and Weathering the Storm in Agriculture: How to Cultivate a Productive Mindset” workshop and can now offer these trainings in New York.

In Minnesota, the MDA also created a three-hour workshop called “Down on the Farm: Supporting Farmers in Stressful Times” and hosted it in six locations across the state. The workshop helped attendees learn what to do when they encounter a farmer in distress. Moynihan said there were about 500 attendees total, including veterinarians, inspectors, bankers, Extension agents, and school counselors and nurses.

Moynihan said that workshop attendees felt relieved knowing what to do when they encounter someone in crisis. The MDA is working with other groups in the state to offer follow-up workshops covering topics like suicide prevention, helping adolescent farm kids in stress, and conflict management.

The Farming Way of Life

When working with farmers and helping them navigate resources, it's important to understand how farm life works and how to convey the importance of mental health to farmers. Matthews in Minnesota has been working with farmers since 1993, so he understands not only the job but the culture. “For farmers, all farmers, it's a way of life that their parents had and their grandparents and their great-grandparents,” he said. “And so, if they can't farm, they lose their identity and that makes it really, really difficult. And so it creates a lot more stress than simply losing your job. You can lose your job and move on, but if you lose your farm, that is really difficult.”

And it's not just the thought of losing the farm that's stressful. Day-to-day operations put a strain on farmers, especially when so many aspects – like the weather and market prices – are outside of their control. Matthews shared how he explains farming to non-farmers: “Imagine what it would be like if you went to get your paycheck and the person who pays you said, 'We had a bad month. You pay me $50'…that's what happens with farmers. They get to the end of the year and, after everything is paid for, they might be in the hole more than when they started the year, even though they worked for 12 months.”

The cost of seeking medical help is also a factor. Moynihan in Minnesota explained that she had tried to avoid the doctor after she lost her employer-based health insurance. For a lot of farmers, she said, “the idea of spending money to go and talk to somebody, that's really difficult, if one of the reasons you're feeling stress and pressure and anxiety is for financial reasons.”

You don't tell people to call Ted the psychologist or the therapist. You say, 'Let's call Ted, who knows more about this than I do.'

Knowing that there's still a stigma around mental illness, Matthews shared how people should recommend his services: “You don't tell people to call Ted the psychologist or the therapist. You say, 'Let's call Ted, who knows more about this than I do.'”

Moynihan shared a story to illustrate Matthews' point: One day when she was running the dairy farm, her loader tractor broke down. She didn't know how to fix it, but she knew who to call for help. Mental health is the same way: sometimes you need to bring in an expert.

Moynihan also knew that, until the tractor was fixed, she could figure out a workaround like using a pitchfork or a skid-steer loader to finish her work. “But if I'm incapable of making decisions or even getting out of bed, if I go down, no tractor in the world is going to make those decisions and solve the problems and get the cows fed for me.”

She added, “I am the most important factor on this farm to making it a success. And so if I don't maintain myself and feed myself well and get enough sleep and get support when I need it, go to the doctor, go to a therapist if I need to…I'm not going to have a chance of running this farm well.”

Additional Resources

- 800.FARM.AID (1.800.327.6243) is a national hotline for farmers.

- Farm Aid's Farm Advocates work with farmers one-on-one to address financial crises, and its Farmer Resource Network online directory helps viewers search for different types of resources by state.

- AgrAbility, a resource for farmers with disabilities, lists mental health resources like helplines, webinars, and national mental health organizations.

- The USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture provides a directory of Land-Grant Universities and Cooperative Extensions. Find your state Cooperative Extension's website by choosing your state and then selecting “Extension” in the Type dropdown menu.

- The National Farmers Union's Farm Crisis Center lists hotlines, mediation and disaster assistance resources, and a drought monitor.

- The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline (formerly the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) is available for everyone, regardless of age or occupation.