Mar 13, 2024

Loud and Clear: Improving Access to Hearing Care in Rural America

by Allee Mead

A married couple arrived at a clinic in rural Vermillion, South Dakota, for a follow-up appointment after both were fitted with hearing aids. The wife thanked audiologist Lindsey Jorgensen, AuD, PhD, for the devices, explaining that her husband can finally hear the squeak in the front steps after a decade of her telling him about the noise. “Three days after we got home,” the woman told Jorgensen, “there is no longer a squeak in our front steps.”

“I always say that my job is 50% hearing aids, 50% relationship counseling,” Jorgensen said. Jorgensen is the chair of the University of South Dakota (USD) Department of Communications Sciences and Disorders and the clinic director of the USD Scottish Rite Speech-Language and Hearing Clinics in Vermillion and Sioux Falls, South Dakota.

The #1 driver that the majority of my patients have in coming to see us is their ability to stay connected with their family members and their friends and their community.

“The #1 driver that the majority of my patients have in coming to see us is their ability to stay connected with their family members and their friends and their community,” Jorgensen said. “As people age, if they can't hear, they become more socially isolated, because it's so much work to go out and hear what's being said.” She added that patients who struggle to hear their provider or pharmacist will struggle to follow instructions.

A 2014 CDC report found that a higher percentage of adults living outside of a metropolitan statistical area reported hearing trouble compared to those living in a small or large metropolitan statistical area. A 2023 article in press for The Lancet also found a correlation between a higher prevalence of hearing loss and smaller population size, with West Virginia, Alaska, Wyoming, Oklahoma, and Arkansas having the highest standardized rates of hearing loss.

While there is a clear need for hearing care services in rural areas, there are significant barriers to accessing this care. A 2017 Laryngoscope article found that rural adults had to drive farther to hearing specialists and waited longer between experiencing hearing loss and receiving hearing devices than urban adults.

Barriers to hearing care

Tribally owned and operated nonprofit Norton Sound Health Corporation (NSHC) serves the Bering Strait region of northwest Alaska, an area covering 23,000 square miles. With one hospital and 15 clinics, NSHC serves a diverse population including the Iñupiaq, Yup'ik, and St. Lawrence Island Yupik peoples. Clinics are run by Community Health Aide/Practitioners (CHA/Ps).

The state of Alaska mandates annual school hearing screenings. Research audiologist Samantha Kleindienst Robler, AuD, PhD, said, “While schools were doing a good job screening, we were not seeing children enter the healthcare system to receive the necessary follow-up care.” Robler's work focuses on increasing access to hearing care in rural and other low-resource areas through telehealth and other service delivery models. In addition, she is currently assistant professor of otolaryngology and associate director of the Center for Hearing Health Equity at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

In order to receive traditional follow-up care, families had to travel by plane, boat, or snowmachine (snowmobile) to the NSHC hospital in Nome. Some families had to first go to Nome and then to the tertiary hospital in Anchorage, which meant another flight and sometimes an overnight stay, which costs money and is more time away from home. In addition, some families are subsistence hunters and can't easily leave home when it's caribou season, for example.

Jorgensen in South Dakota said patients from South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, and Nebraska drive an average of 150 miles one-way to see a practitioner in her clinic. In addition to long drives, patients are taking time off work, having to find child care, and spending gas money to seek hearing care. Older patients may not feel comfortable driving during inclement weather or when it's dark outside.

Jorgensen's clinic offers telehealth, but that service presents challenges of its own if patients have unreliable internet, do not own a computer or smart phone, or do not know how to use their devices for videoconferencing. Jorgensen has also encountered state licensure issues for meeting with her out-of-state patients, low reimbursement for services, and lack of insurance coverage for hearing devices.

Like Robler, Jorgensen said that her state is good at screening children's hearing, but many patients are lost to follow-up care, especially newborn babies. “One of the reasons is you're asking a brand-new parent with an itty-bitty baby to drive for hours on their lack of sleep and having to stop and feed that baby mid-drive,” Jorgensen said.

Telehealth for follow-up care

Jorgensen said that telehealth appointments are better suited for follow-up care, such as making sure that a hearing device fits properly or demonstrating how to clean and check devices, than for initial appointments. In some cases, a nurse in a remote facility (located in rural Aberdeen, Hot Springs, and Winner) can help Jorgensen with the physical setup.

For her out-of-town patients, Jorgensen works to connect them with resources in or near their communities, such as educational, vocational, or age-related services, in addition to talking with their primary care providers and finding support groups.

In Alaska, Robler and her team decided to use telehealth to help students and their families access follow-up care. CHA/Ps were already using telehealth for patients with ear or hearing complaints to connect to specialists in Anchorage or at the NSHC hospital in Nome, but not for preventive care, such as follow-up to school hearing screening.

“With the telehealth infrastructure being as robust as it was,” Robler said, “we thought, well, why couldn't we apply the telehealth we use for acute and chronic care and adapt it for follow-up to a referred school screening?”

Farm safety program for hearing conservation

Another program uses an engaging, hands-on approach to teach rural children about hearing conservation. Jana Davidson is Program Manager at Progressive Agriculture Foundation (PAF). PAF Safety Days educate children ages 4-13 living on farms and ranches and in rural communities on a variety of safety and health topics, including hearing conservation.

If schools or communities choose hearing conservation as one of their topics, children learn three methods to protect their hearing: turning down the volume, walking away from the noise, or using hearing protection. Children receive protection like earplugs and resources to take home to their families.

“Exposing children to safety and health education from an early age is so important in getting them to adopt positive behaviors that they will remember and continue to value as they grow into adults,” Davidson said.

PAF Safety Days can be a standalone program or take place during an event like a county fair, where families can attend. Another PAF Safety Day option is similar to a field trip, where a school's students have a whole day to learn about farm safety.

PAF trains about 400-500 PAF Safety Day coordinators each year. These coordinators serve as the boots on the ground and organize local PAF Safety Days in their communities identifying topics and locating presenters. PAF also works with the 12 NIOSH Centers for Agricultural Safety and Health in the country to make sure that the information they're presenting is current and accurate. “They're the experts,” Davidson said. “They're the researchers pulling it together, giving us answers to why it's important or how this can be done.”

Benefits of hearing care and conservation

Davidson shared a couple stories of PAF Safety Days' impact. She remembered an instructor who noticed one participant's response to the lesson and helped the person and their family arrange a hearing exam. Another participant reported learning the importance of wearing hearing protection while mowing. The PAF website reports that, since 1995, more than 2 million children and adults in 45 states, two U.S. territories, and nine Canadian provinces have been reached.

In South Dakota, older adults receiving Jorgensen's services report taking fewer naps because they're not as tired from straining to hear. Jorgensen mostly serves adults but the clinic serves pediatric patients too. “We've had patients that have been scared when they came here, kids that were not believed, kids that really struggled through school,” she said.

“Sometimes kids were labeled as having behavior problems because they were exhausted by the end of the day from just struggling to hear,” Jorgensen said. After receiving a hearing aid or cochlear implant, the clinic's pediatric patients tend to do better in school and interact more with classmates.

In Alaska, one mother told Robler that her child received tubes in his ears after a hearing screening and telehealth appointment. His speech improved because he could better hear and repeat what others were saying.

From 2017 to 2020, Robler and her team studied their telehealth approach to follow-up care with funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). “What we found is that when telehealth was used, children were more than twice as likely to receive follow-up care, and they received that care 17 times faster,” Robler said.

In the PCORI-funded study, 1,481 students were screened, and 790 of these students needed follow-up care. Within nine months of the initial screening, 68% of students using telehealth had a diagnosis, compared to 32% of students using the standard referral process. On average, students using telehealth had a diagnosis within 16 days, compared to an average of 82 days for students using the standard process. The research team also published their findings in a 2022 Lancet Global Health article, among other journals.

Robler said that some of the communities she studied still face challenges to accessing follow-up care with the telehealth approach. A National Institutes of Health-funded study covering three rural Alaska regions will further research these challenges and ways to adapt the model. Robler said her team hopes to have this model publicly available in 2026, after completion of two implementation trials in Alaska and Appalachian Kentucky. She added that these testing sites don't necessarily have telehealth infrastructure in place, so her team is working on designing a flexible model that accounts for different availability of equipment.

Importance of community and communication

In creating this telehealth approach, Robler said her team also wanted to shorten the typical screening and referral process from an hour to 5-10 minutes while still allowing it to be billable and financially sustainable for the hospital. Her team talked to CHA/Ps and hospital leadership, as well as people who worked in billing, reimbursement, and information management.

For community-based studies like this one, it is absolutely paramount to have community member involvement, engagement, and partnership from the beginning.

“For community-based studies like this one, it is absolutely paramount to have community member involvement, engagement, and partnership from the beginning,” Robler said. Her research team included investigators like her who lived in the area, a stakeholder team, an advisory board, and a Cultural Council. The researchers held focus groups at the beginning and end of the study and conducted over 100 interviews with community members.

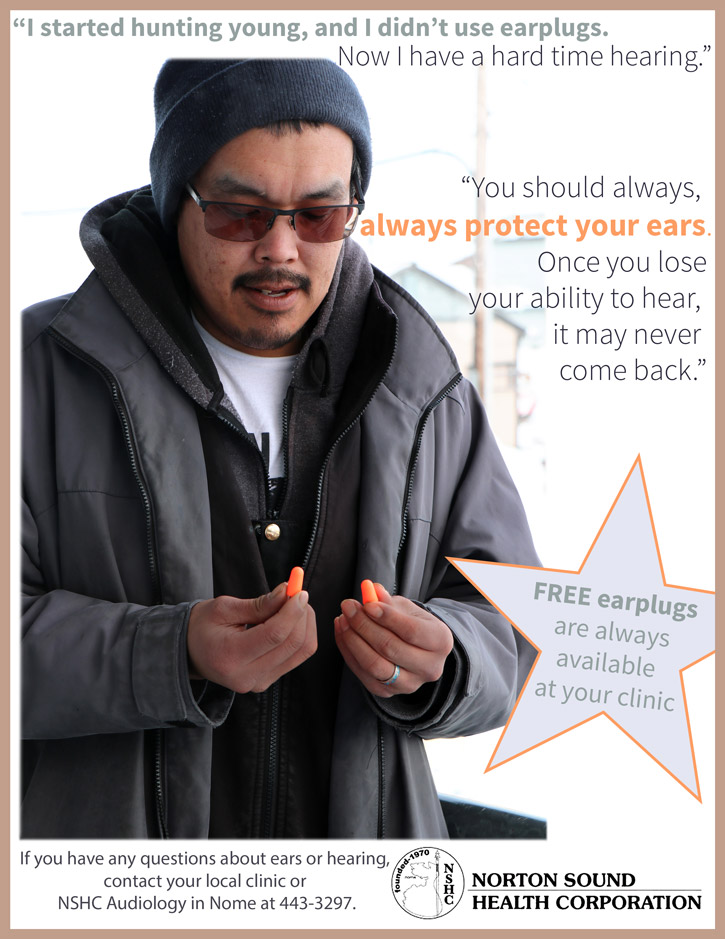

Many community members told Robler they wanted more education and support around noise-induced hearing loss. Regional flyers were made, and researchers added a documentary component to the project so that community members could share their stories, including a hunter with noise-induced hearing loss and a teenager with a hearing device.

Davidson also discussed the importance of sharing stories. She said that the Safety Day lessons can be taught by an expert, such as an audiologist, or by an Extension office employee, but the curriculum is written in a way that allows a layperson to teach it too. Another option is to have someone with personal experience present on the topic. “With hearing safety, you may have someone come and talk about the damage that they caused to their ears over the years by not wearing hearing protection,” Davidson said.

She added that some Safety Days presentations have been taught by teenagers, such as those involved in 4-H or FFA. “It's not another adult telling the younger children what they can or cannot do,” she said. “It's their peers. It's these kids that they look up to.”

Jorgensen in South Dakota discussed the importance of those connections with others: “Our goal is communication competence. I want to make sure that these patients are able to hear to the best of their ability, to communicate how they want. People want that human interaction because that's what a community is and that's what makes those relationships and day-to-day worth it.”