Oct 03, 2018

Trauma Training Initiative Teaches Rural Laypeople How to “Stop the Bleed”

by Allee Mead

On a September day in 2017, a woman's vehicle crossed the centerline and hit a semi on Interstate 94 in West Fargo, North Dakota. She was pinned between her seat and the steering wheel, her scalp bleeding.

A trauma surgeon and a flight nurse witnessed the crash and stopped to help. The nurse tended to the two children in the backseat while the surgeon grabbed hemostatic gauze from her trauma kit and packed the woman's head wound. A third driver who had stopped assisted the surgeon.

Since they were near a large community, trained first responders arrived in 10 minutes. But 40 minutes passed before the firefighters were able to free the woman from the car – a significant amount of time when it comes to blood loss. Thanks to the surgeon's and nurse's quick actions, the woman survived the crash with only minor injuries. Her children were unharmed.

Not everyone who witnesses a crash, shooting, or other injury is a trauma surgeon or flight nurse. But everyone can learn how to stop the bleed.

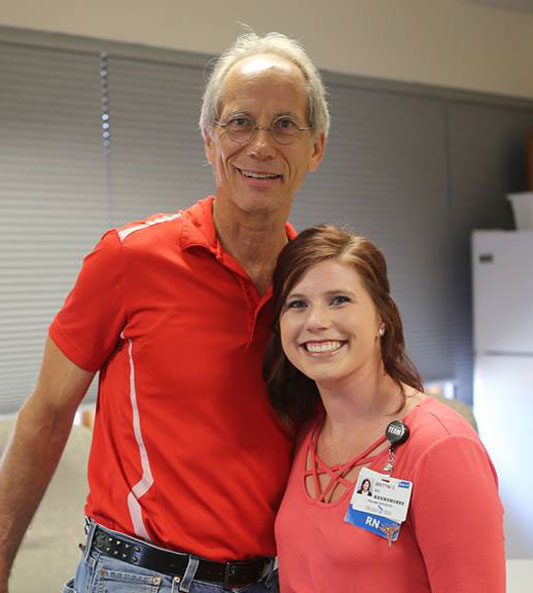

Dr.

Mary Aaland, the trauma surgeon who helped the car crash

victim, teaches Stop the Bleed in

rural communities across North Dakota. A national

training initiative, Stop the Bleed is designed so that

anyone can treat blood loss.

Dr.

Mary Aaland, the trauma surgeon who helped the car crash

victim, teaches Stop the Bleed in

rural communities across North Dakota. A national

training initiative, Stop the Bleed is designed so that

anyone can treat blood loss.

“You don't have to have MD behind your name,” said Aaland, Associate Professor of Surgery at the University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences. “This is for everybody.”

This training is especially beneficial to rural residents who live farther away from the nearest hospital. A 2017 JAMA Surgery article reports that rural residents experience double the wait time for emergency medical services (EMS) personnel to arrive than urban residents: an average of 14.5 minutes in rural areas compared to 7 minutes in urban areas. One in 10 encounters had a 26-minute or longer wait time. But even 14 minutes is too long for someone who is bleeding, so stopping blood loss before EMTs arrive can increase the victim's chance of survival.

From Tragedy to Action

The Stop the Bleed campaign officially began in 2015 but had roots in the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Dr. Lenworth Jacobs, Professor of Surgery at the University of Connecticut and Director of the Trauma Institute at Hartford Hospital, remembers that day clearly.

“We were put on alert for a shooting in a school, and half an hour later we were stood down,” Jacobs said. He explained that this alert cancellation has happened before: for example, if someone reported a gunshot-like sound that turned out to be a firecracker. But this time was a first for Jacobs. “The reason there was no response – no need for medical response – was because everyone was dead. And 20 of them were six-year-olds.”

Since victims had bled to death before EMS personnel could tend to them, the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Board of Regents called on Jacobs and others to form a committee and figure out a way to increase survival from mass casualty events.

The Hartford Consensus devised what Jacobs calls “a three-legged stool.” The first leg involves law enforcement. Originally, the mission was for police officers to secure the scene of a mass casualty event, not necessarily to tend to the wounded. The committee called for law enforcement to receive military-like training so they could treat the wounded as well as secure the scene, like combat soldiers are trained to do.

The second leg involves EMS personnel. Since they don't wear protective gear, they were often told to stay away from a mass casualty event until the scene was secured. But since someone who's bleeding can't wait, the committee had to determine how to improve reaction time while keeping first responders safe.

The third leg involves the public. Since it takes time for first responders to get to the scene of a crime or accident, it's important to train laypeople at the scene to stop blood loss. This leg led to the development of Stop the Bleed.

“So that's really the essence of what we're trying to be: create immediate responders from citizens with a very simple course, encourage emergency medical service people (EMTs and paramedics) to get closer to the scene and start hemorrhage control sooner, and modify the police response to include hemorrhage control,” said Jacobs.

Rural advocates almost immediately recognized the broader application of the Stop the Bleed program in rural areas. Having citizens trained in bleeding control can save lives in an environment where emergency response is hindered by distance, a factor that contributes to high unintentional injury death rates, especially those due to motor vehicle accidents.

Until Help Arrives

You Are the Help Until Help Arrives (also called Until Help Arrives) is a FEMA initiative with a similar mission. People can download training materials or take the course online. Until Help Arrives promotes the following five steps:

- Call 911

- Stay Safe

- Stop the Bleeding

- Position the Injured

- Provide Comfort

Practice Makes Perfect

Stop the Bleed training takes about 45 minutes to one hour. Participants watch a presentation and practice applying a tourniquet to limbs and packing wounds with gauze.

The training kit has two mannequin limbs with puncture wounds. Trainers ask participants to stick their fingers in the wounds to show that even wounds that look small on the surface are much deeper underneath. Placing gauze on top of the wound won't stop the bleeding like packing the wound does. In one ER incident, Aaland from North Dakota remembers using five rolls of gauze for a single wound.

Participants ask her what happens if the gauze gets dirty or if they have to use clothing to pack the wound. While you want to use the cleanest thing available, “you are not going to cause contamination,” Aaland said. “The wound is already dirty.”

She reminds participants that packing the wound or applying a tourniquet will be painful for the victims – but it's better than the alternative. She has them practice what they could say to someone who's hurting: “Listen, I'm saving your life. I know it hurts, but we've got to stop the bleeding. If I don't get this [gauze] in here, you're going to die. Just take a deep breath. You're going to be okay.”

Aaland tells participants that they're not going to make the situation worse by helping. “If you do nothing, he might have a leg, but he'll be dead. You do this [apply a tourniquet]; he might be alive without a leg. But he's alive. That's the whole point.”

Nebraska native Dale Johnson can testify to that statement. In March 2016, he was riding his motorcycle to the grocery store when he was swiped by a car, whose driver hadn't seen him. He flew 21 feet off his bike.

“I knew that my leg was very, very messed up,” he said. “I could start to see my pants turn purple.”

Since Johnson lives in urban Lincoln, the ambulance arrived within six minutes. A paramedic applied a tourniquet, and Johnson received 16 units of whole blood, one unit of blood platelets, and 8 units of other blood products (donations from a total of 23 donors) when he arrived at the hospital.

Since his leg was broken in seven places between his knee and ankle, his wife and the doctors decided to amputate the leg above the knee.

“It was the right decision to make,” Johnson said. “It all goes back to that tourniquet, which gave me a fighting chance to be able to even have a decision made about amputation.”

Since the injury, Johnson has given a talk called “The Only Thing I Lost Was a Leg,” traveled to Machu Picchu, and taken the Stop the Bleed training himself from Brittni Clark, Trauma Outreach and Injury Prevention Coordinator. During the training, Johnson was surprised to learn how quickly someone can bleed out. He realized that even waiting six minutes for the ambulance meant he was “living on borrowed time.”

Having our citizens in our rural areas know how to control that bleeding until EMS can arrive can save so many lives.

“A person can bleed to death in as little as three minutes,” Clark said. “Having our citizens in our rural areas know how to control that bleeding until EMS can arrive can save so many lives.”

Clark has already trained over 4,600 laypeople (about 100 fewer people than the population of Johnson's hometown, Holdrege) in Lincoln and the rural communities surrounding it, including church groups and real estate agencies. She said that Stop the Bleed is also useful for the EMS personnel serving rural Nebraska.

“A lot of our rural EMS are volunteers,” she said. “This campaign gives them the opportunity to actually practice using the tools that many of them know about.”

Ronda Clark, Brittni's mother-in-law, is a physician assistant who also provides Stop the Bleed training in rural York, Nebraska. So far, she's taught 40 to 50 people, including the local Optimist Club and a high school advanced biology class.

She told the high school students, “I've been a PA for 23 years and, outside of the hospital or clinic setting, I've never felt like I needed to use these techniques. And that's a good thing. But luck favors the prepared.”

The training could even help people save their own lives. Aaland, the North Dakota surgeon, remembers treating a farmer who cut his arm on a steel bin and was able to stop his own bleeding: “He put his big old paw in there…told his buddies to load him up and he came [to the emergency room] by his own pickup.”

But his story is a crucial reminder to keep pressure on a packed wound or to keep the tourniquet on: When he arrived at the ER, someone on the medical team removed his hand from the wound, which started to bleed again. Aaland put her finger into the cut and plugged the damaged brachial artery, a large blood vessel in the upper arm.

Increasing Participation Rates to Increase Survival Rates

In addition to performing surgery, leading the Rural Surgery Support Program, and teaching at UND, Aaland provides Stop the Bleed trainings across North Dakota, driving around 26,000 miles each year.

While Aaland has team members who can also teach Stop the Bleed, she likes to provide the training herself. “I enjoy giving the training, because I think it can be more effective when you hear it from a rural trauma surgeon and knowing that you're not doing harm,” she said.

Aaland has trained over 300 individuals so far, with a goal to train 1,000 people per year. She has taught people as young as five (a girl who works on the ranch with her father) and people as old as 90 (a woman whose husband takes a blood thinner). She's also taught National Guard recruits and led classes in Fargo and the rural communities of Hettinger, Langdon, Linton, Tioga, and Watford City.

The ACS Foundation donated over 100 personal Bleeding Control Kits® to Aaland, who distributed them at the Hettinger and Linton trainings. The community of Tioga purchased 100 kits for its trainees. “How often do you get a $70 gift for taking a one-hour course?” Aaland said.

Jacobs from Connecticut wants Bleeding Control Kits to become as ubiquitous as automated external defibrillators (AEDs). He reported that these kits currently sit next to AEDs in urban locations like the Los Angeles International Airport and Gillette Stadium but wants to see the kits in rural areas as well.

Currently, there are 31,398 instructors registered through the American College of Surgeons in 77 countries: 29,855 instructors in the U.S. and 1,543 in other countries. As of September 2018, 403,856 people in the U.S. have received Stop the Bleed training, but Jacobs said that's a low number compared to the country's total population.

Jacobs shares his vision for the training initiative: “If somebody's bleeding, the public knows what to do, they feel empowered to do it, and there's a higher likelihood of survival.”

Additional Resources

- Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences: Stop the Bleed helps users distinguish between serious and non-serious bleeding and learn how to treat both.

- American College of Surgeons: Stop the Bleed provides resources and news stories about Stop the Bleed and helps users: